Introduction to Synchrotrons

By Dr. Matthew Kose-Dunn

Introduction

Synchrotrons are cutting-edge particle accelerator facilities that can generate clean, high-energy x-rays and form a critical segment of the x-ray scientific research market. Researchers use synchrotrons for applications like deciphering protein structures, mapping nanoscale material compositions, and studying chemical reactions in real-time.

Teledyne Princeton Instruments provide advanced x-ray direct and indirect detection cameras tailored for synchrotron use. These cameras excel in handling high-intensity x-ray flux, delivering exceptional sensitivity and resolution for imaging and spectroscopy. Synchrotrons demand robust cameras capable of minimizing noise while withstanding challenging environments, enabling researchers to explore atomic and molecular phenomena with precision.

As synchrotrons continue to unlock new scientific frontiers, our innovative detection technologies empower discoveries in material science, biology, and beyond.

What is a synchrotron?

A synchrotron is a type of particle accelerator, these accelerators propel charged particles (protons, electrons etc.) at close to the speed of light using electromagnetic fields.

Accelerators can be linear in shape (known as LINAC or linear accelerators) but are typically circular, so that particles can be accelerated more efficiently, the x-rays are more stable, and the device can be more compact. Older circular accelerators had constant electromagnetic fields and were known as cyclotrons, but newer facilities synchronize the strength of the electromagnetic fields with the increasing speed of the particles, and as such are known as synchrotrons.

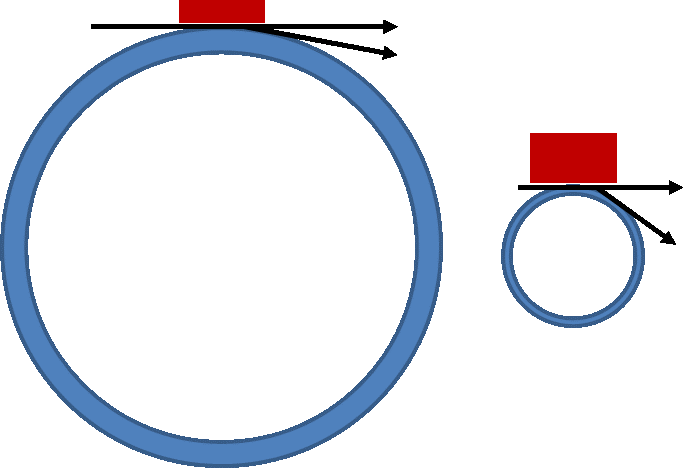

The size of the synchrotron ring is paramount, as the greater the diameter of the ring, the less each magnet needs to bend the particles, as shown in Fig.1. Smaller synchrotrons need more powerful magnets and electromagnetic fields to bend each particle, and consequently are harder to design and more expensive to maintain. While designing a very large ring has higher up-front costs, the running costs are far lower and larger synchrotrons can house more beamlines (the areas where x-ray energy generated by the synchrotron can be used for scientific research). As a result, most modern synchrotron facilities are very large, with the largest being the well-known Large Hadron Collider (LHC), which is 5.4 miles (8.7 km) in diameter.

Figure 1: Synchrotrons with smaller ring diameters require more powerful magnets to bend particles further.

Synchrotrons as light sources

While many synchrotron facilities exist to smash or collide multiple particles together (such as the LHC), some synchrotrons serve as a synchrotron light source. When a charged particle is accelerated to high speeds within a synchrotron, it emits electromagnetic radiation, known as synchrotron light. In particle collision studies this background radiation can interfere and is consequently filtered out, but other facilities rely on this radiation to perform imaging and spectroscopy experiments.

Synchrotron light covers a wide spectrum of energies from infrared (IR) to x-ray. Synchrotron x-rays differ from those used in a typical hospital setting in their brilliance: x-rays produced from a synchrotron are extremely intense (a hundred billion times more intense than a hospital x-ray source), highly polarized, coherent, and emitted in nanosecond pulses. These intense x-rays can be used to obtain extremely precise information, and make synchrotrons highly valuable for researchers looking to perform imaging or spectroscopy experiments with x-rays.

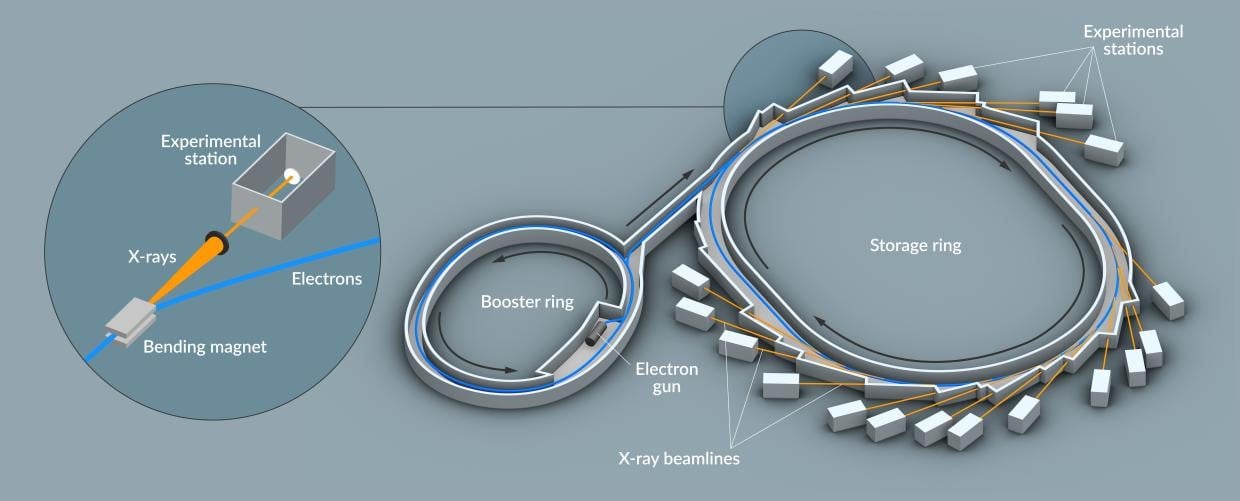

A typical structure for a synchrotron light source is to have one ring to accelerate the charged particles, known as a booster ring, and when these particles are sufficiently high energy to emit intense x-ray energies, they are moved into a storage ring, which houses experimental stations known as beamlines. Each beamline is typically designed to perform different experiments (imaging vs scattering vs spectroscopy, for instance), and receives the x-ray energies when ready.

Figure 2: Synchrotron structure at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. A booster ring accelerates particles until they are fed into the storage ring, which houses the x-ray beamlines and experimental stations. Image courtesty of Greg Stewart of SLAC.

Synchrotron facilities

Synchrotron light source facilities represent a very discrete and dynamic sector, with only ~40 worldwide as of 2024, and many others in development to meet the growing demand for these cutting-edge research facilities.

In this section we will break down these facilities by region. At the time of writing, worldwide synchrotron numbers are as follows:

• Europe/UK – 15 facilities

• Asia Pacific – 14 facilities

• USA/Canada – 7 facilities

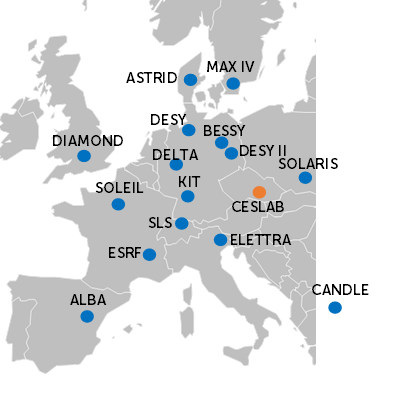

Synchrotron facilities: EU/UK

Figure 3: EU Synchrotrons

Figure 3: EU Synchrotrons

Europe/UK (15 facilities)

• Diamond Light Source - UK

• SOLEIL - France

• European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ERSF) - France

• ALBA - Spain

• Swiss Light Source - Switzerland

• Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron (DESY I and II) - Germany

• Berliner Elektronenspeicherring-Gesellschaft für Synchrotronstrahlung (BESSY) - Germany

• KIT Synchrotron (KARA) - Germany

• DELTA - Germany

• ASTRID - Denmark

• Elettra - Italy

• SOLARIS - Poland

• MAX IV – Sweden

• CANDLE - Armenia

• Central European Synchrotron Laboratory (CESLAB) - Czech Republic, In Development

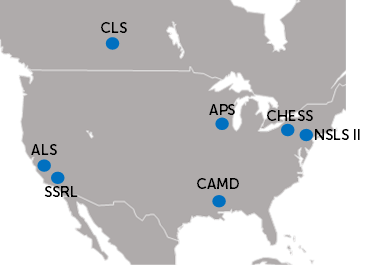

Synchrotron facilities: USA/Canada

Figure 4: USA/Canada Synchrotrons

USA/Canada (7 facilities)

• Canadian Light Source (CLS) - Canada

• Advanced Light Source (ALS) - Berkeley, California

• Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Light source (SSRL) - Stanford, California

• Center for Advanced Microstructures and Devices (CAMD) - Louisiana State University

• Advanced Photon Source (APS) – Illinois

• Cornell High-Energy Synchrotron Source (CHESS) - Ithaca, New York

• National Synchrotron Light Source II (NSLS II) - Brookhaven National Laboratory, New York

Synchrotron facilities: Asia Pacific

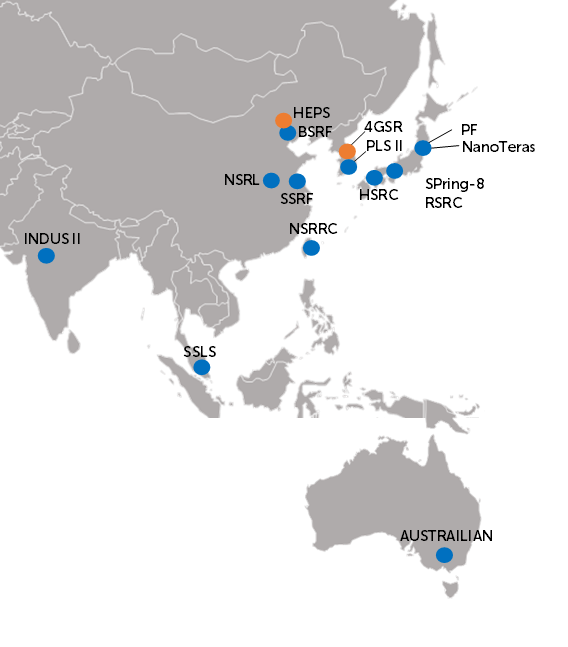

Figure 5: APAC Synchrotrons

Figure 5: APAC Synchrotrons

Asia Pacific (14 facilities)

• Indus 2 - India

• Singapore Synchrotron Light Source (SSLS) - Singapore

• National Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory (NSRL) - Hefei, China

• Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF) - Shanghai, China

• Beijing Synchrotron Radiation Facility (BSRF) - Beijing, China

• Pohang Light Source II (PLS-II) - Pohang, South Korea

• National Synchrotron Radiation Research Center (NSRRC) – Taiwan

• Hiroshima Synchrotron Radiation Center (HSRC) - Hiroshima, Japan

• Ritsumeikan Synchrotron Radiation Center (RSRC) - Kyoto, Japan

• Super Photon ring-8 (Spring-8) - Saitama, Japan

• Photon Factory (PF) and NanoTerasu - Sendai, Japan

• Australian Synchrotron (Melbourne, Australia)

• High Energy Photon Source (HEPS) – China, In Development

• Fourth-Generation Synchrotron Radiation Source (4GSR) - South Korea, In Development

Beamlines

While there may be only ~40 synchrotrons worldwide, each one contains many beamlines. Each beamline is essentially a specialized lab located on the storage ring where the intense synchrotron radiation can be channeled and then directed to specific experimental stations and optical devices.

Typically, each beamline works with a different energy of synchrotron light, and with a specific application, such as imaging or spectroscopy. There can be as many as 50 beamlines per synchrotron.

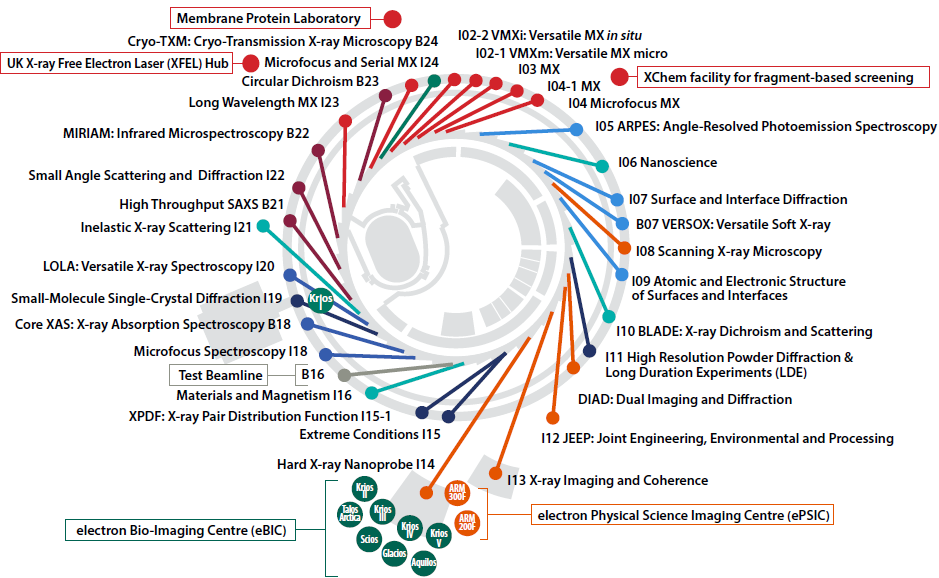

As an example, here is the beamline distribution for the Diamond light source, UK:

Figure 5: Beamlines at the Diamond synchrotron light source, UK. Each beamline is labelled with the specific application and experiments that take place there.

Researchers bid for time on a beamline, receiving a slot in which they can take their samples to the site and gather data. It is therefore vital that each beamline is equipped with highly sensitive detectors so that researchers can answer their scientific questions in the limited time given.

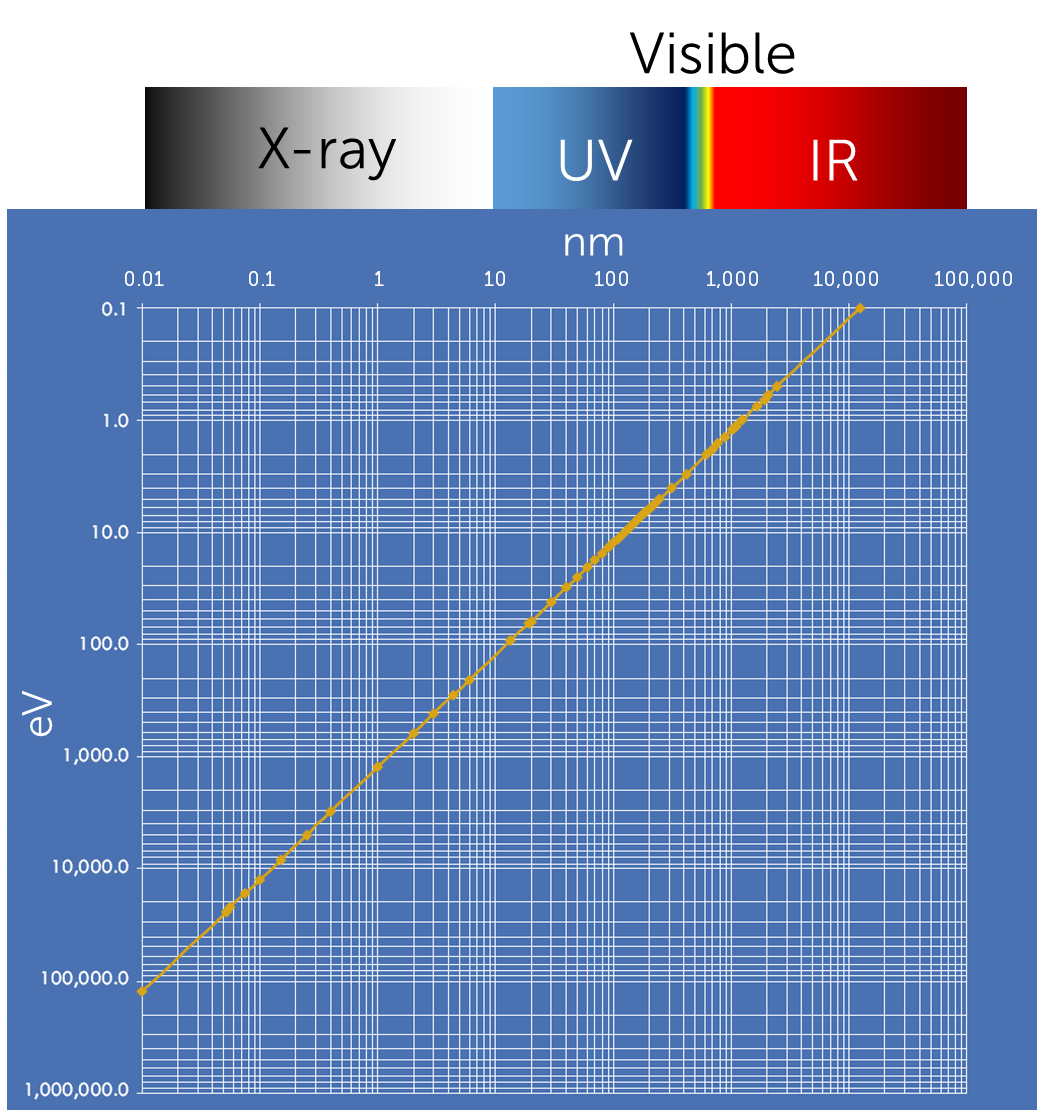

Beamline energy/wavelength

Each beamline can be tuned to an exact energy/wavelength, with some experiments only possible with synchrotron radiation. While some beamlines use infrared (IR), near infrared (NIR), visible and ultraviolet (UV) wavelengths, most use x-ray. Typically, IR/NIR/visible/UV are distinguished using their wavelength, IR/NIR from 3200 – 800 nm, visible from 800 – 350 nm, and UV from 350 – 190 nm.

X-ray, however, is different, typically distinguished by their energy in electron volts (eV), ranging from 100 eV to 100,000 eV (100 keV). X-ray is often further split into ‘soft’ or ‘hard’ x-ray energies, and while the distinction is not well defined, soft x-rays range from approximately 100 – 10,000 eV, with everything else up to 100 keV being hard x-ray.

Hard x-rays are so high energy that they can damage electronics if directly exposed, so whether using a soft or hard x-ray beamline, it is important to use a suitable camera or spectrometer that can detect the appropriate range of energies.

Figure 6: Energy vs wavelength. While UV/VIS/IR are often described with wavelength, x-ray is described with energy in electron volts (eV).

X-Ray detectors

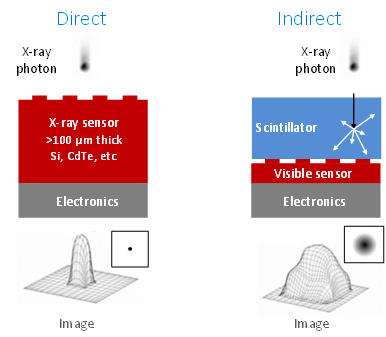

There are generally two methods of detecting hard or soft x-ray energies: direct or indirect. Direct x-ray detectors receive the x-ray energies directly on the sensor, which is typically either a thick (> 100 µm) layer of silicon or another material like cadmium telluride (CdTe) or gallium arsenide (GaAs), and the sensor then converts the x-ray energies into an electrical signal and an image.

The alternative is indirect x-ray detectors, where the x-ray energies first hit a scintillator material which converts the x-ray energies into visible light, and this visible light is then imaged using a camera with high sensitivity in the visible, like a typical modern CMOS camera. Applying a suitable scintillator to a visible light camera essentially converts it into an x-ray camera, but indirect detection has a lower spatial resolution and a time delay compared to direct detection.

In essence, direct detectors feature greater spatial resolution, sensitivity and speed, but work best for soft x-ray energies and are typically more expensive to manufacture. Indirect detectors can image very high energy x-rays at a lower cost, but do so with a lower spatial resolution and decreased image quality.

Figure 7: Direct vs indirect x-ray detection.

At Teledyne Princeton Instruments, we offer a range of direct and indirect detection CCD cameras for soft x ray energies, as well as industry-leading UV CCD cameras and IR/NIR InGaAs cameras, and the latest in modern CMOS technologies for imaging visible light or hard x-ray with a scintillator. We have solutions for the whole spectrum.

Let's have a look at our x-ray detector solutions!

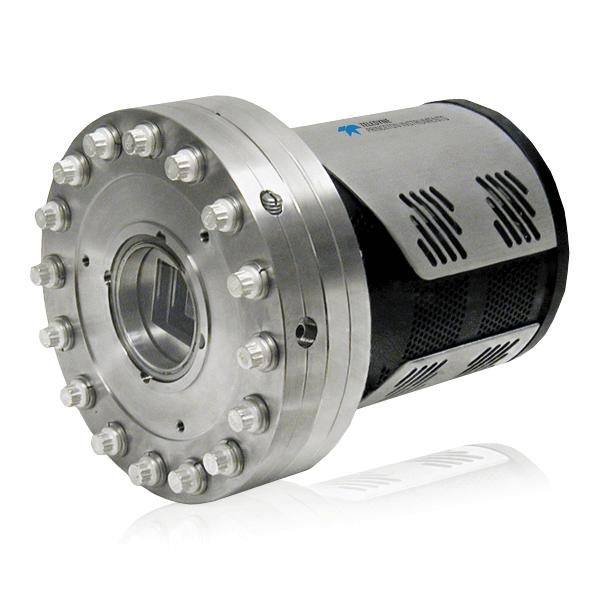

PI-MTE3 (in-vacuum direct soft x-ray detection)

The PI-MTE3 family are large format, fully in-vacuum CCD cameras, designed for direct detection of soft x-rays (sensitive from 1 – 30,000 eV).

SOPHIA-XO (low-noise direct soft x-ray detection)

The SOPHIA-XO family are large format, low noise CCD cameras, designed for direct detection of EUV/VUV and soft x-rays (sensitive from 1 – 30,000 eV).

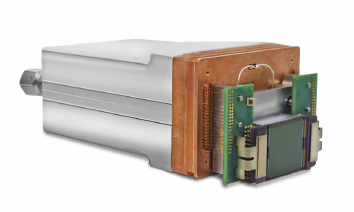

PIXIS-XO (soft x-ray detection for imaging or spectroscopy)

The PIXIS-XO family are CCD cameras designed for direct detection of EUV/VUV and soft x-rays (sensitive from 1 – 30,000 eV), available in either imaging or spectroscopy formats.

PIXIS-XB (soft x-ray detection for imaging or spectroscopy with beryllium)

The PI-MTE3 family are large format, fully in-vacuum CCD cameras, designed for direct detection of soft x-rays (sensitive from 1 – 30,000 eV).

PIXIS-XF (indirect soft x-ray detection)

The PIXIS-XF family are CCD cameras with a unique fiberoptic design and phosphor screen, designed for indirect detection of soft x-rays (sensitive from 3 – 20 keV) once converted to visible light via the screen. Custom phosphors are available upon special request.

IR/NIR/SWIR detectors

A number of beamlines use infrared wavelengths for imaging or spectroscopy. Infrared wavelengths above 1000 nm are very challenging for traditional silicon cameras to capture due to the low energy treating the sensor as effectively transparent. Instead, indium gallium arsenide (InGaAs) sensors feature very high sensitivity from 900-1700 nm, with excellent performance in short wave infrared (SWIR), and the NIR-I/NIR-II windows.

The NIRvana family of InGaAS cameras represent the very best for infrared beamlines.

NIRvana LN (liquid nitrogen cooled InGaAs for SWIR)

The NIRvana LN is the state-of-the-art SWIR camera that offers exceptional sensitivity and stability for challenging low-light applications. It is suitable for researchers who need to capture the faintest signals in the SWIR range with long exposure times with a cryogenic cooling system, hence the 'LN' for liquid nitrogen.

NIRvana HS (high speed InGaAs for SWIR)

The NIRvana HS is the state-of-the-art SWIR camera that offers high speed imaging, up to 250 fps across the full sensor. It is suitable for researchers who need to capture dynamic, rapid SWIR signals without compromising on sensitivity or resolution.